KRLA and the Beat history

KRLA personalities

KRLA specialties

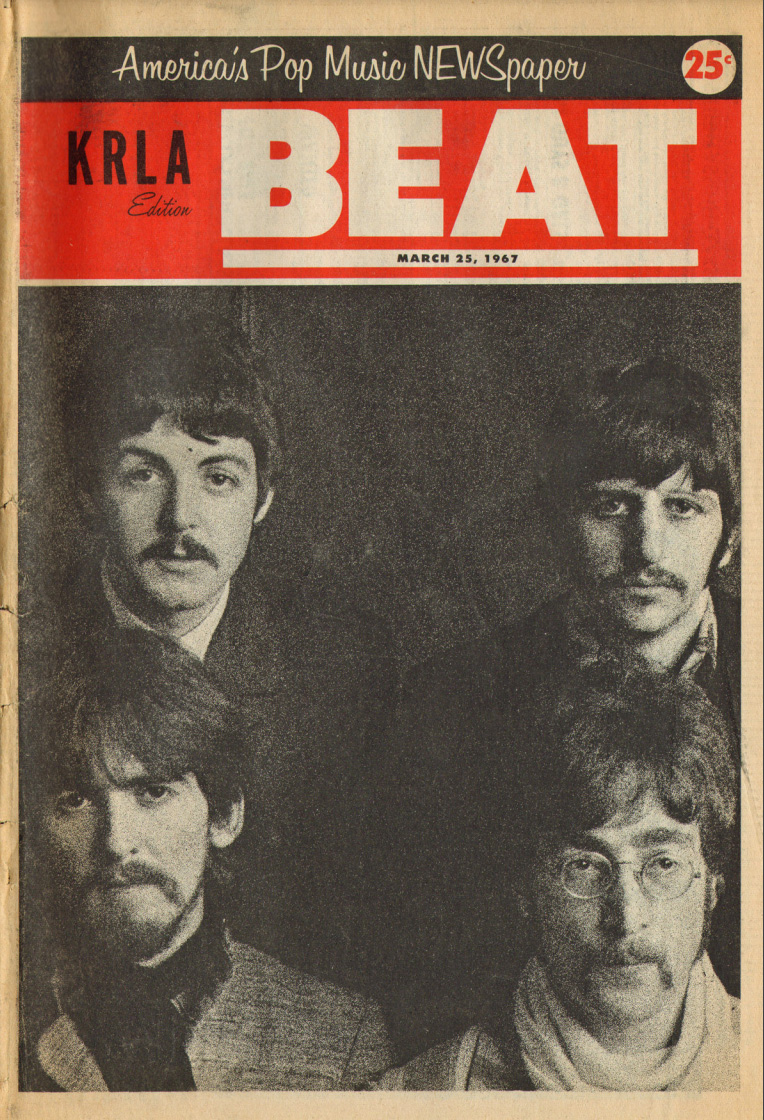

KRLA Beat History

The Beatles were a dream come true for most American Top 40 radio stations in the 1960s, giving new life to tired playlists

and boosting stations' marketing profiles. Beatlemania was also the conduit for a short-lived journalistic curiosity in

Southern California, the KRLA Beat. The newspaper evolved from little more than a four-page promotional throwaway to a

unique, informative music newspaper. Its literary voice strengthened during the several years it was in print, veering

away from bubbly prose about pop groups and offering original articles and photos of some of the biggest names of the day.

The Beatles were a dream come true for most American Top 40 radio stations in the 1960s, giving new life to tired playlists

and boosting stations' marketing profiles. Beatlemania was also the conduit for a short-lived journalistic curiosity in

Southern California, the KRLA Beat. The newspaper evolved from little more than a four-page promotional throwaway to a

unique, informative music newspaper. Its literary voice strengthened during the several years it was in print, veering

away from bubbly prose about pop groups and offering original articles and photos of some of the biggest names of the day.

Self-promotion was undeniably a guiding force in its genesis, but the KRLA Beat had a number of strengths not seen in other regional newspapers at the time. The Beat's format was a harbinger of later publications such as Rolling Stone, which originally used the same tabloid news format. Music weeklies such as NME and Melody Maker were long established in England but the USA had no national U.S. equivalent.

It's true that the Beat wasn't the only newspaper published by a radio station in the Los Angeles market. Rival Top 40 station KFWB ("Channel Ninety-Eight") had been vying for status as the other "official Beatles radio station" and had started up its own 4-page publication about the time the Beat debuted in late 1964. But according to ex-KFWB writer Sue Cameron the Beat led the field...a field where American pop journalism had yet to realize its potential.

What the KRLA Beat had in its favor was a publisher, Cecil Tuck, whose roots were authentically journalistic and whose focus was oriented more toward hard news rather than gossip. Even so, Top 40 was the hot radio format of the era and Tuck admitted that any radio station publication would need to be built around the chart-topping hits and artists of the time.

Tuck had been involved in daily and weekly newspaper production in Texas before moving to Los Angeles and working in radio. As news director of then-Pasadena-based KRLA Tuck hired on-air staff with established reporting skills and in the mid-1960s gave an on-air news platform to the Credibility Gap, a local comedy/political commentary quartet.

One project was the restaging of KRLA's weekly promotional newsletter, originated and developed by Bonnie Golden, a former editor at Teen Screen Magazine. A one-person powerhouse, Golden wrote, designed, and distributed the publication to local music stores and newstands. With KRLA elbowing its rivals for top market status in the Los Angeles area, visibility was key. The station had just sponsored its first Beatles concert at the Hollywood Bowl in August 1964. The KRLA Beat emerged from this mania, evolving from a four-pager in October 1964 to eight pages on newsprint in April 1965. By autumn 1965 the Beat was 12 pages, expanding to 16 pages by the end of 1966.

Once Cecil Tuck took over as publisher in February 1965 he spent much of his first two years not only overseeing operations but also writing, editing, designing, and selling advertising--and not getting much sleep in the process. The paper's logo developed gradually over the months from its original dancing typeface to one adapted freely from the cover of the American LP "Meet The Beatles". Did the paper set out to promote the Beatles because they were the most accomplished group at the time? Not really, said Tuck in a recent interview: "We would have promoted anyone who was popular, it just happened to be the Beatles".

Tuck hired a small staff of writers and reporters, some of whom stayed with the publication during its entire four-year run, to conduct interviews with British and American pop stars passing through Los Angeles. Caught outside the generic milieu of formulaic teen-magazine writing, groups such as The Kinks actually got a chance to muse about their musical influences rather than recite over-used sound bytes. Speaking to Beat reporter Louise Criscione, The Kinks' drummer Mick Avory admitted to seeking out jazz clubs in Los Angeles whenever his band was in town: "I always try to catch great musicians whenever I can, especially drummers", he said in a July 1965 interview. That same issue also reported early attempts to bootleg rock-and-roll recordings played on Radio Free Europe (inlcuding Beatles hits then banned by Hungarian authorities). These bootlegs, the Beat reported, were carried out clandestinely by transferring them not to vinyl but to discarded X-ray film.

In the hands of Beat writers, many articles remained mostly unaffected by tabloid-style gossip, occasionally reporting negatively about favorite bands of the day. An item about the Beatles' 1965 European tour reveals that their concert in Rome was something of a letdown, with only 3,000 Italian fans attending the event in Genoa where the stadium was meant for 22,000.

The KRLA Beat was also fortunate to have Tony Barrow, the Beatles' publicist, as the author of a regular column. Barrow had freelanced before, most prominently in The Beatles Monthly published in England. His columns for the Beat provided up-to-date, substantive news about the Beatles' recording sessions and tours. In February 1967 Barrow gave an early glimpse into recording sessions for the group's next record, "Sgt. Pepper". Barrow also wrote about other British Invasion groups who were then popular on the charts: the Yardbirds, Manfred Mann, the Rolling Stones, even Sounds Incorporated (later to provide brass accompaniment on the Beatles' "Good Morning, Good Morning").

As the decade progressed the Beat's slant included more counter-culture news items with essays about the advent of Haight-Ashbury and LSD. Never a legitimate underground newspaper like its contemporary The Los Angeles Free Press, the Beat nevertheless increased its coverage of the drug culture as it influenced pop music. The arrest of several members of the Rolling Stones was covered in detail, as was Paul McCartney's 1967 interview with ITN in England admitting that he had taken LSD several times. One of Tony Barrow's more ill-timed interviews with Brian Epstein captured the Beatles' manager waxing rhapsodic about the hallucinatory drug experience. "I'm wholeheartedly on its side" proclaimed Epstein to Barrow. Within a month Epstein was dead from an accidental drug overdose.

Another former member of the Beatles' echelon was Derek Taylor, then based in Los Angeles to manage several local music groups such as The Byrds. Taylor wrote columns for the KRLA Beat from early 1965 through 1968, not always credited but with an unmistakable voice of authority. He was soon acting editor for the paper. Having Taylor on board also dovetailed nicely with Cecil Tuck's developing view of a pop journalism "empire", encompassing other major radio markets across the country. San Francisco station KYA was an early partner in the venture, using the Beat template and providing local reporting for their own editions of what they called the KYA Beat.

Derek Taylor was already heavily involved in promoting the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. Under his editorial tutelage the Beat's reporting, as well as its graphic design, shifted toward the psychedelic, emphasizing color graphics and photography. Stories began to lean toward "generation gap" journalism and music coverage emphasized West Coast groups like Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead, supplanting a previously steady stream of stories about the Beatles. By 1968 Tony Barrow's byline was seen less often, if at all.

Derek Taylor himself was growing disenchanted at the helm of the KRLA Beat. Never happy when Cecil Tuck heavily edited his verbose but charming writing style, Taylor was also distressed at having to adhere to a publishing budget. Tuck recalled that Taylor "ran up an incredible amount of expense" in 1968 when each issue was set to cost no more than $2,500 to produce. The resulting decision was painful but inevitable: Tuck was forced to let Taylor go in mid-1968.

Faced with increasing production debt, Tuck kept some stalwart reporters on staff, but news items in the Beat began to originate with wire services as well as standard Hollywood press releases. The sparkle and bite of the Beat's style began to dim. Advertising revenue remained tepid. Unable to interest other radio stations in the newspaper, Tuck was forced to consider selling the Beat to the highest bidder. Two music industry names expressed an interest: Dick Clark of "American Bandstand" fame, and Mike Curb of the music group The Mike Curb Congregation. But their intent was to fold the Beat entirely and recoup their investment losses with tax write-offs. Tuck reversed his decision to sell and kept the newspaper barely alive until spring 1968, when it folded for good after an unscrupulous distributor absconded with all remaining funds.

Over the years Cecil Tuck continued to work in the field of radio news production and managed a consulting business until his passing in 2021. Erstwhile Beat reporters seem to have mostly vanished or, if writing still, have gone on to other bylines. When copies can be found, issues of the KRLA Beat sell on the collector's circuit for anywhere from $25 - $50 each. They still provide a unique glimpse into pop music's past and one of the first nascent awakenings of rock-and-roll journalism.